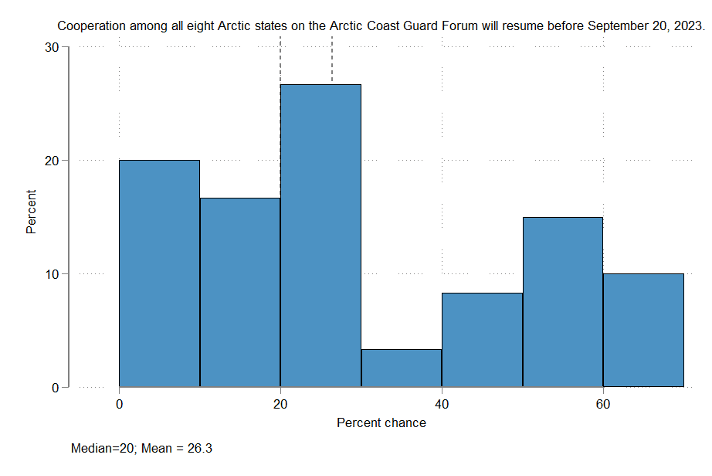

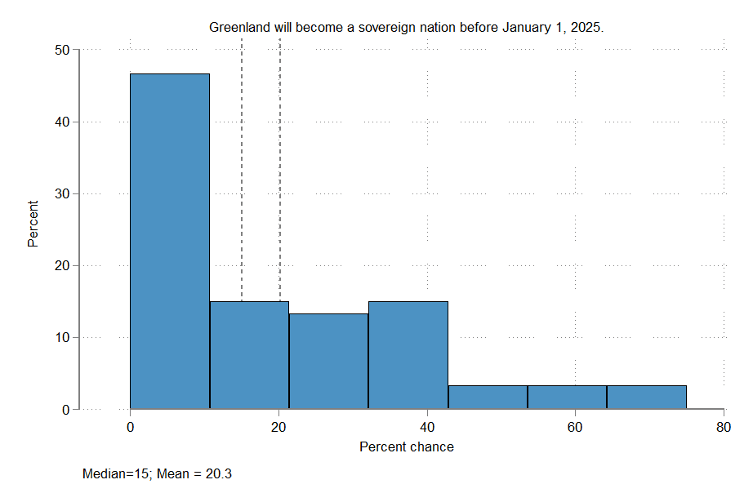

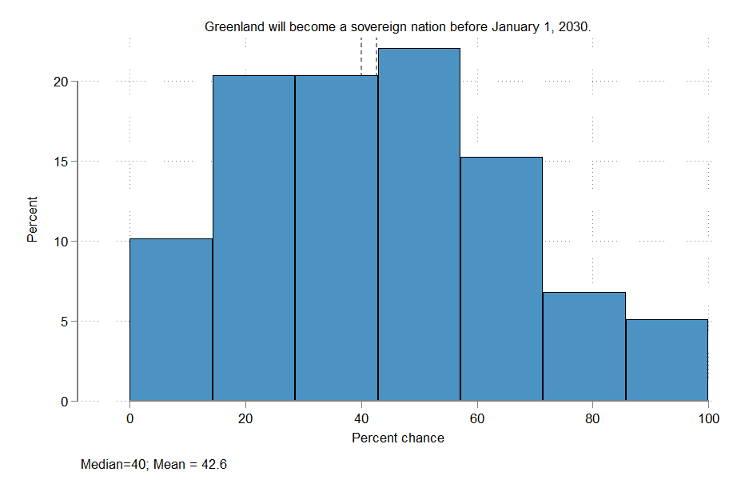

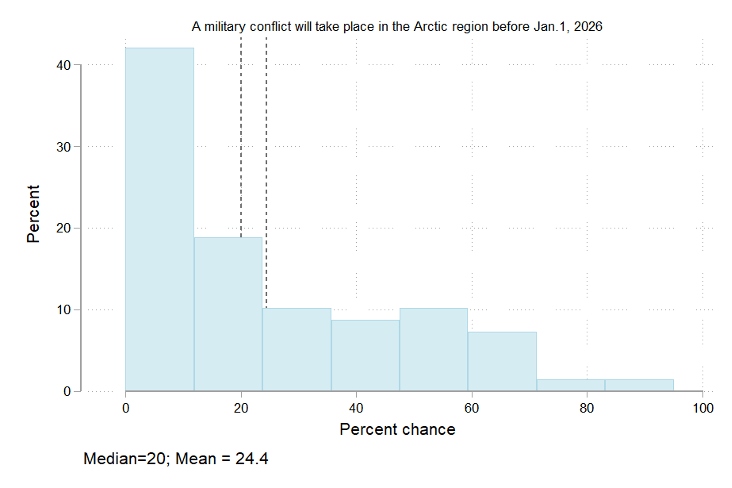

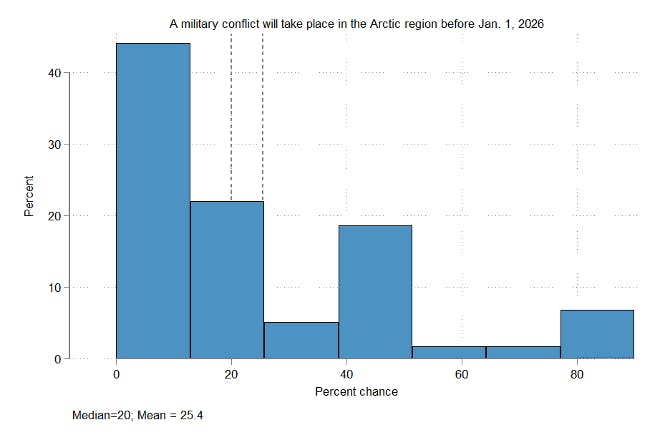

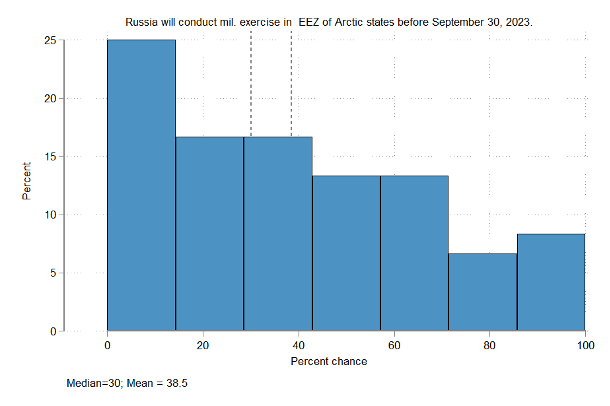

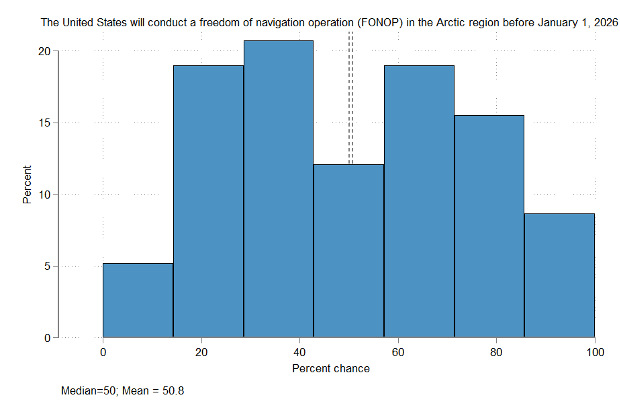

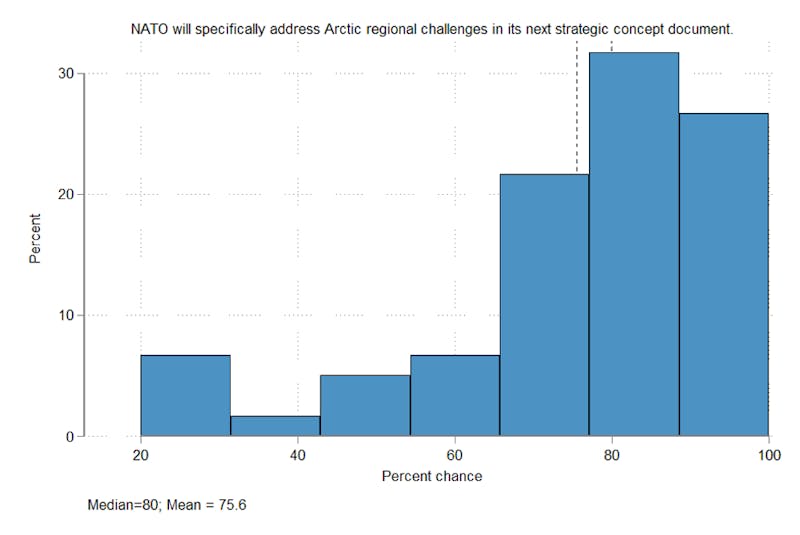

The future of the Arctic region is dependent on several structural forces, the most important being climate change, but geopolitical dynamics are increasingly coming to the fore and institutional cooperation is currently hampered. The future of the region is also highly contested and subject to much speculation, some predicting a race, a struggle or both simultaneously while others predict a more orderly and stable development. As a result, we decided to organise a survey asking Arctic experts their predictions about the likelihood of possible Arctic geopolitical developments. This method has considerable advantages. First, we sought to capture regional expertise, collective wisdom and consensus rather than relying on isolated assessments of experts reading the region’s oracle. Secondly, we were able to capture the developments that experts see as most likely rather than gathering normative assessments of whether a described development was desirable or not. Hence, the objective is to assess where the areas of consensus emerged and which perceptions were dominant on key governance and security questions. Moreover, we want to build a time-series on important issues to track possible changes in the perception on, inter alia, Arctic security and governance.

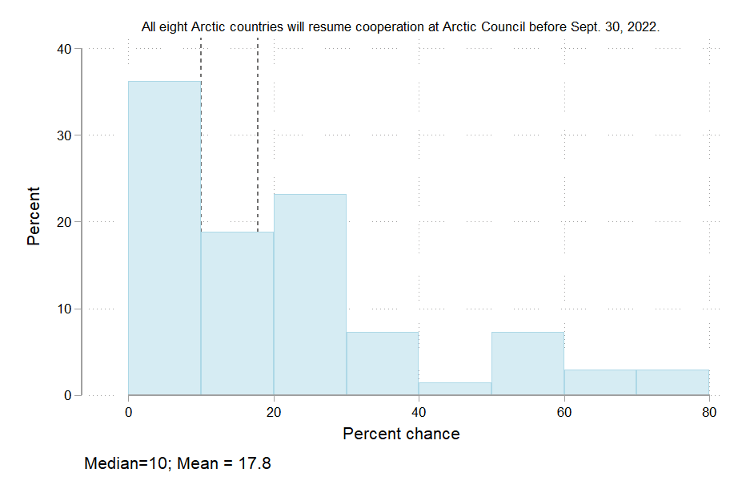

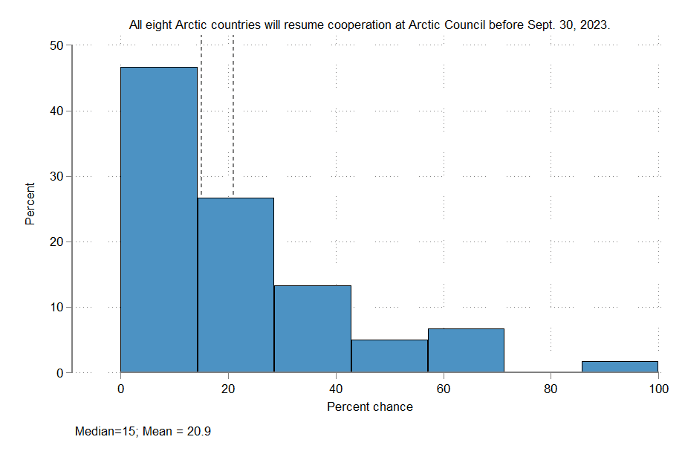

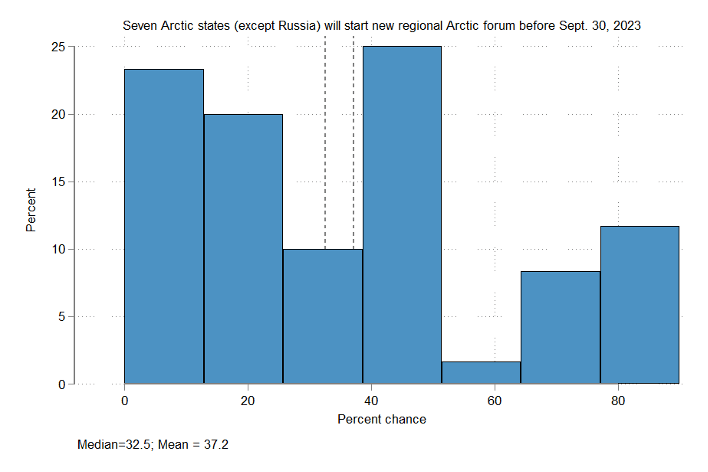

We conducted the first wave of this expert survey in June 2022 reaching 69 respondents and a second wave in January 2023 gathering 60 responses. We adopted a broad definition of Arctic experts, one encompassing academics, governmental officials, civil society representatives. We asked experts to rate from 0 (impossible to happen) to 100 (certain to happen) the likelihood that certain Arctic developments might occur. Some observations emerged out of these two waves.